Ballintemple: Dark Knights, Blue Bells

by Turtle Bunbury

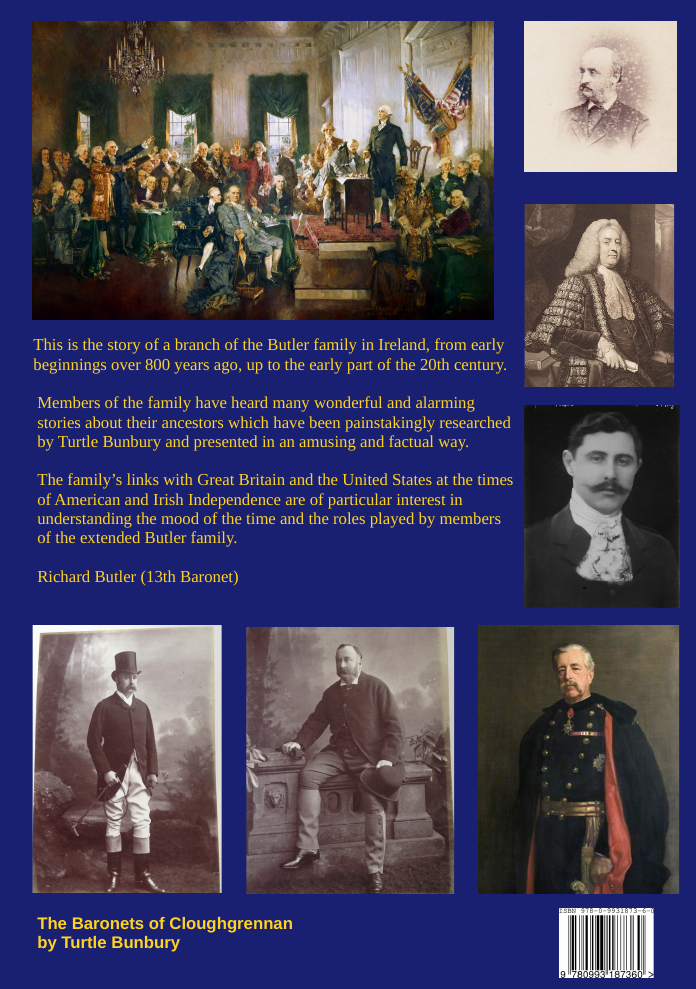

Major Pierce Butler had been living in America for close on 20 years when he embarked on his first return trip to his Irish homeland in the summer of 1785. Life on the 41-year-old Carlow man’s plantations in South Carolina had been increasingly awkward ever since the outbreak of war between the colonists and the British Redcoats who sought to govern them. Within a year Major Butler would be among those who gathered in Philadelphia to sign the US Constitution. Shortly before he embarked on his journey across the Atlantic, he wrote to a friend of his excitement at seeing his birthplace once again. “Ballintemple! What an Irish name!”

Major Pierce Butler had been living in America for close on 20 years when he embarked on his first return trip to his Irish homeland in the summer of 1785. Life on the 41-year-old Carlow man’s plantations in South Carolina had been increasingly awkward ever since the outbreak of war between the colonists and the British Redcoats who sought to govern them. Within a year Major Butler would be among those who gathered in Philadelphia to sign the US Constitution. Shortly before he embarked on his journey across the Atlantic, he wrote to a friend of his excitement at seeing his birthplace once again. “Ballintemple! What an Irish name!”

Ballintemple is of course an Irish name, an Anglicized version of Baile an Teampaill, indicating that Major Butler’s family home stood upon the site of a sanctuary or settlement attached to an ancient temple. Little remains of this temple today but Lewis’s invaluable Topographical Dictionary of Ireland states that, in 1837, there was at Ballintemple “the ruins of an old church, beautifully situated on the margin of the River Slaney”. All the signs suggest that the original temple at Ballintemple belonged to the Knights Templar. This extraordinary, often controversial military order was established by the Papacy in 1118 to protect pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem. They arrived in Ireland in the wake of the Norman invasion of 1169 and secured strategic properties throughout the country. At this time, Carlow formed part of the Irish inheritance of the great Norman magnate, William Marshall. Shortly before his death in 1216, he was made an honorary knight of the Order. It is my belief that William Marshall donated the lands at Ballintemple to the Knights Templar for use as a sanctuary. The site made practical sense. The nearby village of Aghade, one of the few fordable points across the Slaney, was an important pass between the Norman strongholds of Wexford and Dublin. One of the benefits of being a Templar was exemption from payment of the hefty toll taxes levied at fords such as Aghade. Working in conjunction with the Cistercians at Duiske Abbey, the Knights of Carlow built castles at Killerig, Leighlinbridge, Bagenalstown and Tullow. Over the course of the 12th century their power and wealth soared throughout Europe. On Friday 13th October 1307, King Philip of France launched a campaign to eliminate the all-powerful Knights Templar from the contest. The Pope, a prisoner of Philip, conceded to their excommunication on allegations of rampant heresy. Untold thousands were swiftly arrested and imprisoned; hundreds were burned at the stake. Many fled underground or joined the army of Robert the Bruce in Scotland where they would go on to play a pivotal role in securing an epic victory for the Scots over the English at Bannockburn in 1315. And then they disappeared, almost without trace.

Although the history of the Knights Templar was much censored over the course of the Middle Ages, their stories rapidly became the stuff of legends. It seems likely that their name still conjured a great deal in popular imagination when their former sanctuary at Ballintemple was granted to an off-shoot branch of the great Butler House of Ormonde. It is not clear when exactly Ballintemple was so-granted but it was probably a 17th century initiative, made at the behest of the Great Duke of Ormonde to his cousin, Sir Thomas Butler of Cloghrennan. Sir Thomas' Father, Sir Edmund Butler had grown up, with his more famous brother “Black Tom” - the Earl of Ormonde, in England in the same household as the future Queen Elizabeth. Loyalty to the Houses of Tudor and Stuart paid off when Thomas was elevated to the peerage by Charles I in 1628. In due course, he found himself centre stage of the Confederate Wars. His cousin, the Earl (later “Great Duke”) of Ormonde convened a large royalist Confederate army at his castle at Cloghrennan (near Milford) in 1649. The army was duly annihilated by the English at Rathmines and Cloghrennan Castle blown apart by Cromwell’s canons. Sir Thomas and his wife, Lady Anne, were arrested and held prisoner in Kilkenny Castle. Lady Anne later recalled the waters of the River Barrow filled with the bloated carcasses of slaughtered innocents.

The restoration of Charles II and the House of Stuart in 1660 would have stood the Butler family in good stead. Sir Thomas’s cousin, the Earl of Ormonde, was created Lord Deputy of Ireland and, in 1682, elevated to the Duchy. Would this enlightened soul not have rewarded his long-suffering kinsman with a grant of lands, perhaps even the lands on which the Knights Templar once gathered? The lands at Ballintemple had been part of the vast estate purchased by Ormonde’s forefathers in the late 14th century. The Duke must have been aware of the Knights Templar, perhaps through his friendship with Charles II. In 1680 he founded the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham as a home for wounded army pensioners. Symbolic or not, Kilmainham was itself a former stronghold of the Knights. The family survived the upheavals of King James II’s fall in 1691 intact, no doubt helped by their Protestant faith. Sir Thomas’s grandson, also Sir Thomas, represented Carlow as an MP from 1692 until the death of Queen Mary in 1703.

The chief hazard of writing the history of Ballintemple House is that scant little information about the house survived its burning in 1917. Thus we do not know when it was built, who built it or even which of the family commissioned it. That said, it is my belief that the original house of Ballintemple was built for Sir Richard Butler, 5th Bart, father of the Major Butler who fought in the American Revolution. He stood as MP for Carlow from 1729 to 1761 and married a cousin of the Duke of Northumberland. 18th century MPs were wont to devote their latter years to overseeing the construction of magnificent new homes that might reflect their lifetime achievements for centuries to come. Such properties were erected throughout Carlow at this time – consider Burton Hall (1730), Viewmount House (1750), Beechy Park (1750s), Duckett’s Grove (pre-Gothic, 1760s) and Browne’s Hill (1763). Sir Richard was a man of considerable wealth and political prowess. He would have required a sizeable house for a family of four sons and six daughters and perhaps, as befitting the age, he decided to build a new home at Ballintemple. It is certainly relevant to note that the parish records in Aghade state that (Major) Piers Butler was born “at Ballintemple” on 11th July 1744.

All that remains of Ballintemple today is a classical portico through which the Butler family and their guests once entered and exited the big house. It seems likely that this stylized entrance was a later addition to the Georgian building, probably added in the wake of the Act of Union when the landed gentry began rebuilding and updating their houses with renewed vigour. An estate of some 6500 acres centred on Ballintemple came into the possession of Sir Thomas Butler on the death of his father, the 7th Bart, in 1817. His eldest son and heir, another Sir Thomas, wrote an intriguing journal chronicling his time with the 56th Regiment in the Crimean War while a young man.

Life went full circle for the Butlers when one afternoon in 1899 a young American heiress introduced herself to Sir Richard Butler, 10th Bart, as Alice Mease, great-great-granddaughter of Major Piers Butler. In due course, the two married; their grandson is Sir Richard, the present Baronet. Alice wrote of Ballintemple as “one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen … it had a thousand acres and three woods: the upper, the middle and the lower. In front of the comfortable Georgian house rose a high terraced bank of rhododendrons which, when in full bloom, and the sun setting behind them, looked like a red river. At the bottom of the third wood flowed the River Slaney, somewhat like a s Scottish river, tumbling over brown mossy rocks and full of salmon … In the spring the woods were literally carpeted with bluebells, the bluest and largest I have ever seen, often having fifteen bells on one stalk.”

Surviving photographs indicate that Ballintemple was a three storey Georgian house of much elegance. Above the ground, there were 25 rooms, the principals likely set aside as bedrooms for family and guests, drawing room, dining room, library, nursery and so forth. A large basement supported servants quarters, pantries, laundry, cellarage and other fundamental basics to the running of a good household. The cleanliness, sustenance and education of the Butler family was orchestrated by a sizeable team of tutor, housekeeper, cook, parlour maids, housemaids, footmen, valets and – of course – the Butler’s butler. Fruit and vegetables was supplied from a 4 acre walled garden a half mile from the house, secured from rabbits by a wall 12 foot high and 4 foot thick.

The Butlers were progressive landlords, keen to enhance the quality of their lands and so improve the lot of their tenant farmers. At its peak, the farm was one of the most complete in the south of Ireland, comprising farm house, dairy, laundry, stables, forge, saw mill, stables, three sunken cottages and several cottages for farm labourers, gardeners, grooms and – eventually – a chauffeur. Wheat, potatoes and other crops were grown on the land; livestock was primarily sheep and pigs. In the early 20th century, Sir Richard Butler, began breeding a large herd of black Aberdeen Angus whilst simultaneously cultivating a smaller herd of Clydesdale shire-horses. It is believed more than 20 families derived their income from working at Ballintemple right up until its tragic burning in 1917. At peak times such as hay-making, potato-picking, harvesting and threshing, dozens of seasonal labourers were also recruited.

The burning of Ballintemple in 1917, attributed to a plumber’s blow-lamp and dry-rot filled rafters, was a great loss to Carlow’s architectural legacy. The shell was later demolished and only the 19th century portico remains. Subsequent confiscation’s and compulsory purchases by the Irish Land Commission whittled the Butler estate down to a few acres and a former garden house. But the Butler family continue to view Ballintemple as an intrinsic part of their family heritage in the 21st century. Sir Richard has been concentrating on the opening of several fishing lodges along the banks of the Slaney; his eldest son, Tom, is developing a modest organic farm. Standing at Ballintemple today, listening to the rushing waters of the Slaney one is carried back through the course of time to an age when, perhaps, veterans of the Crusades ambled along these same forested riverbanks, their feet carpeted in bluebells and wild daffodils.