Prisoner of War Escape

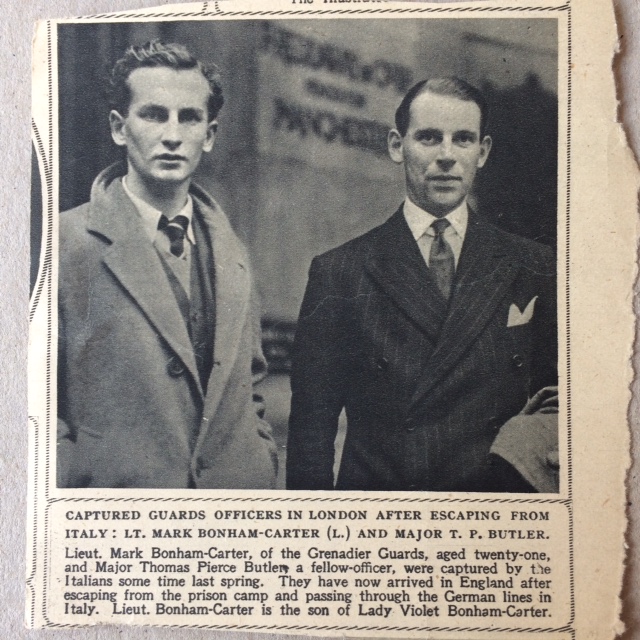

(An escape from Italian prison by two officers of the Grenadier Guards - Thomas Butler and Mark Bonham-Carter. Edited from the original by Sir Thomas Butler.)

Our camp was in Northern Italy and there were there some thousand Officers together with about three hundred O.R.s who acted as cooks, messmen and servants. The camp was surrounded by a ten foot wall on top of which was a barbed wire fence sloping inwards. At various points along the well were built up platforms on which were mounted M.G.s sited to fire along the wall and powerful search-lights. Outside the well beyond a narrow path was another barbed wire fence. A patrol used to walk from time to time along the path between the wall and the fence. No one was allowed to approach within ten feet of the wall and at night It was brilliantly floodlit.

Plans for escaping were continually being hatched and early in September there were two tunnels well under way; One of these aimed at hitting off the main town sewer which ran across the corner of the camp and came out In the canal well outside the well.

The two main difficulties were cutting a way into the sewer wall and the other was of being able to exist long enough In the sewer Itself to cut through the Iron grille which guarded Its exit Into the canal.

As it happened neither tunnel was completed although the sewer wall was reached and In one case breached ‑ the stench was appalling.

On the evening of September 8th the news came through that the Italians had signed an Armistice. The whole camp went crazy and a free issue of marsala was handed round. Everywhere the wildest rumours spread like lightening. It was officially announced that Allied landings had taken place at Spezia ‑ Livorno and as far north as Genoa.

After a conference with the Italian Commandant the senior British Officer told us that his latest instructions from the War Office were that we were all to stay put. The Commandant was awaiting orders from Rome and meanwhile the Guards would remain at their posts to protect us against any Interference from the Germans. No one slept a wink that night. Many of the P.O.W.s had been 2 years in captivity. Early next morning it was noticed with amazement that our Italian Guards were doing the vanishing trick over the well, having exchanged their rifles for a suitcase. Their Officers made a feeble and an entirely hopeless effort to stop them. The S.B.O. at once went into conference first with the Italian Commandant and then with his own senior officers. He then issued a statement to the effect that "all communications with Rome had ceased and no further orders had been received therefore he would no longer forbid anyone to leave the camp although he himself and his staff were remaining and he strongly advised us to do the same".

As he finished speaking the Germans arrived and proceeded to take over the camp having locked up all the Italian Officers in the local gaol. The Germans assured us that there was no intention 0 f moving us and they were only safeguarding themselves. Our hopes were soon dispelled by the arrival, the next day, of a German Colonel who described himself as O.C. removal of P.O.Ws to Germany. He told us that as soon as he could obtain transport, we were to be moved to Germany.

Meanwhile tunnelling went on night and day in a desperate attempt to reach the sewer. In the small hours of the next day extra guards and transport arrived and shortly afterwards some eight or nine hundred P.O.Ws had left the camp en route for Germany. We had dodged this party but a bitter blow was in store for us. Our living quarters within the Camp consisted of six large stone bungalows, three each side of the Camp, and these in turn were each divided off into four large stone floored wards with a corridor down the centre. After the departure of the first party the rest of us were herded into two of the bungalows on the opposite side of the Camp and away from our tunnels; this meant of course these schemes had to be abandoned.

No further movement took place the next day. In the evening we received a message from some friendly Italians outside the Camp telling us that if some of us wished to escape over the wall that night, they would distract the attention of the sentries manning the M.G.s. They would signal with lighted cigarettes as soon as the patrol had passed on its rounds. This message was followed by a pair of' wire cutters hurled over the wall. . A courageous South African decided to make the attempt and zero hour was fixed for 10 PM. At exactly 10 o clock the signal was given and Lt. X climbed the floodlit well and started to cut his way through the wire on top. For fully five minutes he sat astride the wall while at each end the sentries were being plied with wine and engaged in conversation. A mouse would have been visible on that wall and the sentry had only to glance along it and squeeze the trigger of his Spandau to riddle the man on top with bullets. At last the job was finished and he dropped down the other side, crossed the path, and passed through the gap in the outer fence made by the Italians. Two others followed but the third was recaptured by the Patrol.

Earlier in the day another fine escape had been made which was a brilliant piece of quick thinking and nerve. Some children, playing in a field outside the camp, picked up a live grenade which exploded. badly injuring one of them. The injured child, followed by several weeping relatives, was brought into the Camp Hospital. Twenty minutes later, when the relatives walked out of the main gate, they were accompanied by a British Officer dressed in civilian clothes and holding a handkerchief in front of his streaming eyes!

Meanwhile a plan was forming in our minds which was simply to find a really good hideout and, when the remaining P.O.Ws were moved, to just disappear in the hope that eventually the Germans would leave the camp or at least remove the sentries from the well.

A hole had been constructed, large enough to take two people lying full length, under the tiled floor of one of the rooms. An ingenious lid was made of the tiles and this fitted exactly over the entrance and an iron bedstead was placed over the top. Finally a supply of food, water and some civilian clothes was hidden In the hole.

The next morning orders were issued for the rest of the camp to get ready to move with the exception of the Hospital and a rear party of about sixty who were to remain behind to clean up the camp. The two of us managed to be busily engaged in sweeping up one of the rooms when this party left. That afternoon those that were left were again moved to another bungalow. At 5 AM next morning we lined up, with our baggage and, while waiting for the transport to arrive, we left the others and strolled over to the bungalow where our hideout was. We reached the room and, to our horror, were confronted with three German soldiers sitting on the beds talking. Making the excuse that we were looking for something we beat a hurried retreat and rejoined the others. Soon afterwards we noticed the Germans leave the bungalow and we again managed to walk over without attracting attention. We reached our hideout and disappeared from view.

As time went by we began to realise just what we were in for in this frightful hole. To begin with there was no air and, after a few hours, we were both gasping for breath and nearly suffocating. Every time we removed the lid of our hole the noise seemed deafening and we felt that the Germans, who were still moving about in the building, could not fail to hear us. In addition we discovered, to our great discomfort, that our hole was a home for hungry mosquitoes who seized upon every exposed portion of our face and hands and devoured us.

At one moment a German came into our room in search of loot and sat on the bed above us while another played the piano in the next room for over an hour. It was only during the night that we could with safety crawl out of our hole to get some air and to stretch our limbs. To sleep was impossible. We had a feeling that once we slept the air in our hole would be used up and we would never wake. In the other bungalows we could hear shooting and supposed that our German friends were either drunk or searching for P.O.Ws in hiding.

Early next morning we heard German troops moving about for a short time and then for two hours there was silence. We crept out of our coffin and had a look round. The sentries were no longer guarding the wall ‑ the M.G.s had gone but round the other side German transport was still in the Camp near the main gate.

In a few minutes we had changed into civilian clothes and collected a water bottle and a bag containing food, socks and washing kit. In a few more minutes we had climbed the wall and the wire and were free. We only learned later that the Germans had kept a patrol on outside which by the grace of God we had eluded.

Our escape had been made over the north well of the Camp and It was necessary to make a long detour to bring us round towards the south. The plan was to head for Florence some eighty miles away. This meant crossing the Apennines but we felt that if Allied landings had indeed taken place north of Rome, British troops would have occupied Florence by the time we had travelled those eighty miles. It wasn't until many days later that we discovered how untrue our information had been.

The sun was our only guide for we had no compass, no proper map and no watch between us nor was our disguise complete as one of us was still wearing khaki drill trousers. We later exchanged these for some really old patched trousers belonging to a farmers and a couple of hats that no tramp would deign to wear.

The first essential was to put as great a distance as possible between ourselves and the Camp. After waiting for a German convoy to pass, we crossed the main road, and went like scalded cats across the vineyards towards the mountains. By sunset we had covered approximately 18 kilometres. Each day we walked from sunrise to sunset always across country. Roads were barred owing to German M.T. and M/C patrols. Sometimes we covered twenty five or even thirty kilos a day, more often no more than sixteen or eighteen especially when we found ourselves amid the high peaks of the Apennines. The going was very rough and we were lucky if we found a mule track of loose stones leading in the right direction. Ploughed fields were a nightmare to us and even the mountain sides are ploughed up in Italy.

Each night we sought out some lonely peasant's cottage or farm and begged shelter In the cow barn or loft. When this was refused, and it only happened on two occasions, we were compelled to sleep in the woods. This happened once at 5000 ft and we had no coats and no blankets. More often my companion's Italian obtained us a billet in the straw with the oxen. Sometimes the straw was clean but usually it was infested with rats and every conceivable bug. Permission to sleep on the straw always included as a matter of course, the evening meal with the family usually at least ten in number. In one tiny house we found two couples living with fifteen children and a grandfather. This evening meal was our one proper feed of the day and generally consisted of macaroni or potatoes with possibly some tomatoes added. During the day we would visit farms to obtain information about Germans in the vicinity and about our route.

We seldom left a house without a hunk of bread made from meal and a piece of cheese made from the milk of goats or even sheep. In the valleys fruit was plentiful and the vineyards were laden with grapes. our chief trouble was drinking water. The national drink is wine and, except in the mountains, fresh water was difficult to obtain. However we got used to anything after a while. Hot drinks, such as coffee, cocoa, or tea were unknown, as was tobacco. The Germans had removed it all, as well as boots, leather/grain cattle, poultry and wool. They used to raid a village or a house and remove everything after destroying what they could not take away. One poor peasant had just finished making his year's 'Vino' which he was going to sell and which was his only livelihood. One day a German soldier came along and demanded a glass of wine. After drinking it he opened the vats with his bayonet causing all the wine to run out on to the floor. It is not to be wondered at, that the people of Italy fostered such a burning hatred against the Nazi army. Parties of Germans with no excuse at all would raid a village. blow up a home or two, shoot a couple of women and smash every wireless set that they could lay hands on. This was all happening before Italy's declaration of war on Germany.

It wasn't until we were across the mountains and only twenty five miles from Florence that we learnt that there had been no landings north of Salerno and that our armies were still several hundred miles away. In the area of Florence, we were told there was a German division, and the west coast was alive with troops, so we decided to go East and make for the Adriatic Coast. This meant crossing the Apennines again, this time from West to East. It was near here too, that we began to meet real terror among the Italians. A few days before a Priest had been shot for helping escaping P.O.Ws. A proclamation had been issued in the papers and stuck up in towns declaring that anyone found helping a P .0 W. in any way would be shot and that anyone turning in a P.O.W. would receive a reward of 1,800 lire or £20 sterling. So we took to the mountains again and the poor people helped us if there were no Germans in the vicinity. We spent nights as the guests of Charcoal Burners high up on the wooded slopes, of Millers grinding their grain by some river and even of an Italian poetess who wrote religious poems in a school next to an old Church perched on the top of a mountain.

When we came to a river we would wade across, avoiding the bridges which were often guarded. Some times it was possible to have a swim and wash our socks and shirts. Our journey took us across six major rivers and many smaller ones. By this time we had acquired an excellent map and consequently travelled much straighter but wet days with no sun would cause us to go astray. On our travels we met many other fugitives. Most of them were young Italians returned from Yugoslavia having given their rifles and M.G.s to the Slavs, or from Croatia or Albania. Some were just ordinary Italian soldiers disbanded and endeavouring to avoid being conscripted for labour by the Germans. A proclamation had been issued calling up all classes between 1910 and 1925 for labour In Italy. Fear that they would be sent to Germany had caused a general exodus of the young men from the towns and there had been practically no response to the German order.

We spent one night in a lonely shepherds hut, where we met with strange company. The party consisted of two R.A.F. P.O.Ws, two Yugoslavs, one Italian soldier, and a free French Arab and none of us could speak the others' languages.

One day we reached a famous Franciscan Monastery 4000 ft up on a pinnacle of rock and there we were entertained by the Monks to a splendid meal.

The Fascists were a continual source of danger to us. More so even than the Germans, because they were impossible to identify. In most villages and districts a few Fascists would completely dominate the population. They were hated by all but, backed by the Germans, they were all powerful. At one place two Fascists had been beaten up by the local people and the next day German troops had arrived and shot some and burnt the houses of others.

One of our many worries was whether our boots would hold out. Both pairs had been as good as new at the start of the journey but after three weeks of incredibly rough going, one pair had no toe caps and the other no soles. In the end both pairs just held out after 400 miles but they would go no farther. They had been repaired six times.

As we approached the German defensive lines our difficulties increased and several times trouble was only just avoided. We entered one village from the North as some Germans come in by the South and only a timely warning saved us from an awkward encounter.

As we crossed the Sangro river we could hear extensive demolitions and from one hill we watched the Germans blowing up a railway bridge. Once we came unexpectedly on a road, unmarked upon our map, and found it blocked for miles with M.T. A convoy was refuelling. The petrol dump was very visible in a huge red brick building just down the road at a junction. We lay for two hours in sore rushes until the convoy had left and then crossed the road. Two days later we had the immense satisfaction of being able to give the exact map reference of this patrol point and our bombers were sent over with, I hope, excellent results.

|

| Thanks to Gardner Cadwalader, cousin from Pannsylvania, who shared this news clipping kept by his Aunt Sophie. |

A little further on we were talking to each other loudly in English when we come upon two German soldiers standing in a form yard. Luckily they took no notice of us!

Quite near where we fancied the front line ought to be we saw. a 'jeep' moving along a road. We hung about and were nearly caught by a lorry load of German troops, The 'Jeep' of course was a captured one.

Nearing the river Trigno, the Germans seemed everywhere and there were very few lonely houses from which we could get information so vital to us nor were the farmers working in the fields.

Twice we went towards cottages only to find, just in time, signal wires leading up to the door. Once a farm, pointed out to us as unoccupied, was found to harbour German troops digging defences close by. The heights overlooking the river were sprinkled with gun positions and O.P.s. Our passage of the river itself made us sick. with fright. The river bed was nearly 300 yards wide but with only a thin channel of water in it - even so we had to remove our trousers to wade across this channel. However, no one bothered about us.

Once across the river the wonderfully welcoming sound of our own guns fell on our ears and we could mark the shell bursts.

The ground here was covered with tracks of German tanks and A.T.V.s but the vehicles themselves seemed to have gone.

On the 15th of October, exactly 30 days since we climbed over the wall of our prison, we reached our own lines having covered just over 400 miles.